Neuroplasticity Unveiled: A Nonpharmacological Approach to Reducing Behavioral Psychological Symptoms of Dementia

Submitted by Amy Roberts Huff, Melinda Hermanns, Sandra Petersen, Barbara Chapman

Neuroplasticity is the ability of neurological networks in the brain to change through growth, revitalization, and reorganization (Carey et al., 2019). Neuroplasticity is impaired by Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroplasticity may help the brain to compensate for some of the behavioral psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) damage caused by Alzheimer’s disease, a degenerative disorder that affects neurons that regularly remodel. Therefore, lifelong Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) is important to maintain optimal brain health and decrease the risk of dementia (Diniz & Crestani, 2023). It is the BPSD that makes many caregivers overwhelmed as 90% of all patients with dementia exhibit BPSD. CST has been found to decrease BPSD in patients with dementia (Anantapong et al., 2025). A nurse can easily implement CST to treat patients suffering from dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Review of Literature

Examination of the scientific evidence of neuroplasticity in age-related neurodegenerative diseases specific to Alzheimer’s disease and dementia will be discussed along with evidence based targeted nonpharmacological interventions to support brain health in the aging population. Neuroplasticity has been found to be effective in retraining connections in the brain. Cognitive Stimulation Therapy is the modality of how neuroplasticity occurs. CST use in dementia is well established and recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] (2018) and the Alzheimer’s Society to be incorporated by 2024. There are several CST therapies that have been shown to reduce the rate of decline by six months or more with people with mild to moderate dementia (Carbone et al., 2021). Many studies had single component CST programs. A Cochrane review found further study is needed regarding how a multicomponent program that takes the best of the research on CST to decrease the rate of decline in mild to moderate dementia (Woods et al., 2023). One of the more difficult problems of caring for patients with dementia is the BPSD that 90% of the patients with dementia will exhibit in their disease process. Nonpharmacological interventions present a safer and more cost-effective option to control BPSD rather than adding more medications which can have drug to drug interactions and adverse effects of neuropsychic medications (Cho et al., 2023).

Disruption in neuroplasticity is evident in age-related neurodegenerative diseases contributing to cognitive decline (Karamacoska et al., 2023). Over the years, a dichotomous view of neuroplasticity and scientific evidence has evolved. However, scientific advancements have demonstrated the brain’s dynamic ability to retain its natural ability for plasticity and reorganization in late adulthood. While the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease remains misunderstood, causations have posited accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques. Recent studies identified a decrease in soluble beta-amyloid (Rogers, 2023; Sturchio, 2022).

Neuroplasticity should be conceptually understood as a balance between upward and downward connections in the brain (Diniz & Crestani, 2022). Density levels and structural complicity of brain components (dendrites and spines) should be considered part of a neuroplasticity program rather than a deficiency. Thus, comparable to how a puzzle fits together, upward, and downward neuroplasticity complement each other so the brain can effectively reshape connections to optimize the network’s efficiency as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Neuroplasticity

Note. In Diniz, C. R. A. F., & Crestani, A. P. (2023). Neuroplasticity [Figure 6]. Creative Commons – (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

CST is needed in dementia and Alzheimer’s care. The Alzheimer’s Society and NICE recommend that by 2024 all memory services should have access to CST. The use of multicomponent CST has been identified as effective but needs further research. Research has shown that CST has improved cognition, mood, and ability to do activities of daily living. CST results in a six month decrease in the progression of dementia (Woods et al., 2023).

Other diagnostic tools for dementia includer neuroimaging, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) also aid in understanding the structural and functional changes in the brain and age-related and dementia related plasticity. Animal studies are offering promising research to support the potential of positive nonpharmacological interventions to promote neuroplasticity (Colavitta & Barrantes, 2023; Shaffer, 2016). The concept of neuroplasticity is based on the premise that a person’s brain can create new connections, change, and compensate for damage caused by a disease. For example, nonpharmacological interventions including environment, physical activity, and learning skills, i.e., practicing new and existing skills can improve neuroplasticity through a process called synaptic plasticity that strengthens neuronal connections (Carey et al., 2019). Environmental activity and cognitive stimulation have been shown to promote neuroplasticity. Evidence demonstrates that cognitive training using guided practice on structured tasks has been shown to increase neuroplasticity and promote global cognition (Woods, 2023). Bagattini and colleagues (2020) found that cognitive function improved with a combination of transcranial magnetic stimulation and cognitive training. The interventions will be three times a week as this is shown to be the most effective interval (Woods, 2023). Increasing the brain’s ability to adapt may offer continued benefits in the aging population to help decrease or prevent cognitive decline.

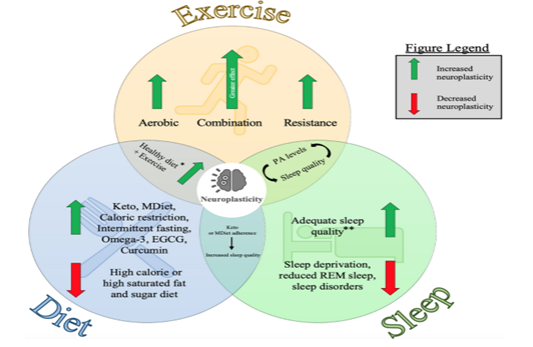

Neuroimaging tools identified the brain volume in the prefrontal and hippocampal was larger in those engaged in physical activity early in life, findings confirmed by consistent, longitudinal studies. The role of nonpharmacological interventions to promote healthy lifestyle changes, include healthy eating, proper sleep, and aerobic exercise to support brain health, cannot be underscored (Shaffer, 2016). Evidence-based outcomes continue to highlight the benefits of targeted nonpharmacological interventions including exercise activity, diet, sleep, stress reduction, and cognitive training to support neuroplasticity in older adults. Figure 2 further depicts the influences of the three nonpharmacological interventions.

Figure 2.

Diagram Representing the Individual and Combined Influences of Exercise, Diet and Sleep on Neuroplasticity

Note. From Pickersgill, J. W., Turco, C. V., Ramdeo, K., Foglia, S. D., & Nelson, A. J. (2022). Diagrams represent the individual and combined influences of exercise, diet, and sleep on neuroplasticity. [Figure 1]. Frontiers in Psychology 13, 831819. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.831819. Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

While CST is one of the more popular evidence-based interventions for people with dementia (Carbone, 2021), we believe a multicomponent CST consisting of three areas that focus on the best evidence for CST (Sikkes et al., 2020). These three focal areas of Connect, Move, and Learn can be implemented by nurses, physical and recreational therapists, and caregivers.

Connect: This includes music therapy. Music therapy has been found to decrease depression, improve social behavior, increase communications when people struggle with words, and increase quality of life (Vandersteen, 2025). During music therapy patients can play an instrument, choose the music, sing along to music, or just listen to the music.

Move: Structured physical exercise, aerobic exercise, and resistance training or a combination of these has a positive effect on global cognition (Erickson et al., 2019) and neuronal adaptations, memory, and executive function. Exercises of 12 weeks have shown effectiveness in slowing cognitive decline in people with cognitive impairment (Karamacoska et al., 2023; Kraal, et al., 2021). Research has found that cross body exercises utilized in cerebrovascular accident (a stroke) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) have resulted in cognitive improvement and overall function. Since dementia and progressive neurocognitive diseases result in similar neuronal death it is hypothesized that such interventions may help in dementia. Cross body exercises that cross the midline of the body increase neuroplasticity and will be included in the exercise portion of all move sessions (Sun, 2019).

Learn: This is cognitive stimulation therapy which provides stimulation for enjoyable activities that stimulate thinking, concentration, and memory (Sikkes et al., 2021). These activities will focus on social stimulation and have been shown to improve quality of life and cognitive function. Learning is done in a group setting to increase socialization (Woods, 2023). Learning will focus on new activities to stimulate the brain. Reading clubs, name tunes, name and explaining the pictures, what to pack for a picnic to go to the beach, crossword group puzzles, discussing countries, discussing history, or making a recipe book are activities that can facilitate learning. Reminiscence therapy will be utilized in the connect (music portion) and in the learning portion of our proposed study. Reminiscence therapy has been shown to potentially reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, and improve cognitive functioning (Yanagida et al., 2024). Reminiscence therapy will include reconnecting with older memories through movies, topics of the past, and explaining family photos to the group.

Economics of Treating Dementia

The economic impact of dementia is very costly in several ways. Caregivers will lose earnings as they care for the person with dementia, often referred to as informal costs. There are the formal costs of medications, treatments, and at times residential care which are referred to as formal costs. It is estimated from 2010 to 2050 that the number of individuals with Alzheimer's disease (AD) who are over 70 years of age will increase by 153%. The worldwide economic burden of dementia care is $1.3 trillion. In the United States (U.S.) alone the cost of caring for Alzheimer’s and dementia is $360 billion. If dementia were an economy, it would be the 17th largest economy in the world (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2025). The cost effectiveness of CST with dementia has been shown to be effective (Knapp et al., 2022).

Insurers pay the formal costs and 75% of these formal costs are paid for by Medicaid and Medicare. In 2050, the total cost of caring for one patient with AD will be $511,208. If there can be delayed the onset of AD by five years this will result in a 40% lower cost of AD by 2050 (Zissimopoulos et al., 2015). A person who lived from 70 years old to 80 years old with AD will spend 40% of this time in a severe stage. At the age of 80, 75% of the people with AD live in a nursing home. An estimated 66% of people who die of dementia do so in nursing homes (Alzheimer's Association, 2024).

The cost of care for AD was substantiated by Aranda in 2021 as in the U.S. alone, combining formal and informal costs of care all persons with AD were estimated to be greater than $500 billion in 2020; and, in 2050 this is expected to raise to $1.6 trillion when adjusted for inflation. Nandi (2022) found higher projections on the world economic cost of dementia. Countries with low and middle income will account for 65% of the economic burden of ADRD by 2050. Nandi (2022) believes there is a higher figure for Alzheimer's Disease Related Disorders (ADRD) care worldwide in 2050 at $11.3 to 27.3 trillion. Nandi (2022) also estimates the cost of ADRD in 2050 will be $1.6 trillion. One reason for this increased cost of care is that people are living longer. In 1970 the average life expectancy was 60 years old, in 2017 this increased to 72.7 years, and it is expected to rise to 82 years by 2075. Based on these projected estimates the cost of care for AD is unsustainable and we must find ways to delay the onset of AD and ADRD (Brück et al., 2023).

There are economic impacts based on race. In the U.S., more whites and women live with AD. Black and older Latinos are disproportionally more likely to have ADRD. Population projections by age, sex, and race from 2015-2060 indicate that over 43% of Black people and 40% of Latinos have the greatest burden of ADRD diseases (Matthews, 2019). The estimated total economic burden of ADRD for African American and Latino adults was $113 billion in 2020 and was projected to reach $1.7 trillion by 2060 (in nominal dollars), surpassing the economic burden for White adults, which was projected to grow from $231 billion to $1.4 trillion. African American and lutino caregivers to adults with ADRD were estimated to be more adversely financially burdened by care provision than White caregivers, and this difference was projected to grow further in the coming decades (Mudrazija et al., 2025). Women tend to live longer with dementia than men (Aranda, 2021). The lifetime cost for women are costs were three times higher than men due to women both having a longer duration of illness and spending more time in a nursing home (Yang, 2015). White (2019) looked at the Medicare expenditures of Dementia and concluded that dementia is one of the costliest conditions to society (Velandia et al., 2022).

Insurance is a problem for those with dementia as Medicare does not pay for dementia care, just end-of-life care for those with dementia. Medicaid is the only public program that will pay for long-term care for those with severe AD (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024). The out-of-pocket costs are larger for a person with dementia (32%) than for those without dementia (11%) (Russell et al., 2017). For long-term care that is provided at home Medicaid pays for 43% of services, followed by Medicare (22%), and private insurances cover only 9%. The rest of the expenses are covered by other sources, and this often means payments from caregivers, patients, or families (Colelo, 2021).

The latest data on the cost of care from the Alzheimer’s Association in 2022 revealed the median cost of care for a non-medical home aide was $5,358/month. Adult day cares average $81/day assisted living residencies was $56,068/year, nursing homes were $112,556/year for a private room, and $98,534/year semi-private (Genworth, 2024). The private long-term care insurance market consolidated since 2000. In 2000 41% of policyholders were insured by one of the five largest insurers (National Association of Insurance Commissioners, 2016).

The following case study is one example of a nurse implemented CBT in an inpatient memory care unit.

Case Study

Harry was an 82-year-old Black male with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. His family was supportive, but Harry continued to decline over the six years since his diagnosis, becoming wheelchair bound. He suffered a stroke approximately two years ago, leaving him with left side weakness and minimally verbal. Harry’s family provided care at home for him until the stroke occurred but soon found that the burden was becoming too great for their 79-year-old mother who had her own health issues. The family began looking at various facilities for placement and decided upon Mountain View Assisted Living and Memory Care.

Mountain View held a unique approach to memory care, promoting the use of neuroplasticity to help residents retain and regain skills. Taking a minimalist approach to the use of medication, the staff at Mountain View utilized aromatherapy to help calm residents and help them engage in programming activities. Harry’s family learned that staff used peppermint oil in cool diffusers to heighten alertness prior to program activities. The community used a sequence of activities based upon neuroplasticity concepts through engaging emotions (right side of the brain), movement (cross the body exercises) and then reminiscing. Before meals, the community used cueing with citrus scents to stimulate appetite; warm moist oshibori towels heated in lemon water were used by the residents to clean their hands. The citrus scent stimulated neurotransmitters in the stomach and increased appetites.

The move into assisted living memory care was not an easy decision for Harry’s family, but they were hopeful that the move would allow their mother to regain her health and provide socialization and care for Harry. When Harry first moved to Mountain View Assisted Living and Memory Care, he was reluctant to participate in programming. Staff diligently brought him to neuroplasticity training throughout the day; Harry sat quietly and did not appear to engage. Staff used passive range of motion with Harry during exercise sessions to see if “muscle memory” might be stimulated. Initially, staff and family saw few signs that Harry might be able to join in.

Then, one day while Harry sat passively in a reading group, it happened. The group was reading a book about the history of M&M’s candy, and it was Harry’s turn. The group facilitator looked at Harry and asked if he would like to read. Harry initially sat quietly, then, suddenly, he began to speak softly; then, slowly, with more confidence read, “M&Ms were made in only a few colors: red, green, and brown”.

All eyes were on Harry as a big smile spread across his face. This breakthrough was only the first of many to come for Harry as his brain began to respond to the brain “enlivening” that took place using neuroplasticity. Over time, Harry’s behavioral medications slowly decreased, as he became more successful and active in the community.

Conclusion

Neuroplasticity has been found to be effective in retraining connections in the brain. Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) is the modality of how neuroplasticity occurs. There are several CST therapies that have been shown to reduce the rate of decline by six months or more with people with mild to moderate dementia (Carbone et al., 2021). Many studies had single component CST programs. Further research is needed regarding how a multicomponent program that takes the best of the research on CST to decrease the rate of decline in mild to moderate dementia. The incidence of dementia is increasing and the cost of treating dementia is immense. Nonpharmacological approaches to treatment of dementia are cost effective and delay the progression of dementia for six months (Woods et al., 2023). Incorporating CST that focuses on connecting, moving, and learning multimodal therapy is needed for at home care and inpatient care to combat the progression of dementia in our patients.

References

Alzheimer’s Association. (2024). Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures special report: Mapping a better future for dementia care navigation. https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf

Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2025, July 7). Dementia: Facts & figures. https://www.alzint.org/about/dementia-facts-figures/

Anantapong, K., Jiraphan, A., Aunjitsakul W., Sathaporn K., Werachattawan N., Teetharatkul T., Wiwattanaworaset P., Davies, N., Sampson, E. L. (6 Jan 2025). Behavioral and psychological symptoms of people with dementia in acute hospital settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing, 54(1), afaf013. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaf013. PMID: 39888603; PMCID: PMC11784590.

Aranda, M. P., Kremer, I. N., Hinton, L., Zissimopoulos, J., Whitmer, R. A., Hummel, C. H., Trejo, L., & Fabius, C. (2021). Impact of dementia: Health disparities, population trends, care interventions, and economic costs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69(7), 1774–1783. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17345

Bagattini, C., Zanni, M., Barocco, F., Caffarra, P., Brignani, D., Miniussi, C., & Defanti, C. (2020). Enhancing cognitive training effects in Alzheimer’s disease: RTMS as an add-on treatment. Brain Stimulation, 13(6), 1655-1664.

Brück, C., Wolters, F., Ikram, A., & de Kok, I. (2023). Projections of costs and quality adjusted life years lost due to dementia from 2020 to 2050: A population-based microsimulation study. Alzheimers & Dementia, 19(10), 4532-4541. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13019

Carbone, E., Gardini, S., Pastore, M., Piras, F., Vincenzi, M., & Borella, E. (2021). Cognitive stimulation therapy for older adults with mild-to-moderate dementia in Italy: Effects on cognitive functioning, and on emotional and neuropsychiatric symptoms. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(9), 1700–1710. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbab007

Carey, L., Walsh, A., Adikari, A., Goodin, P., Alahakoon, D., De Silva, D., Ong, K. L., Nilsson, M., & Boyd, L. (2019). Finding the intersection of neuroplasticity, stroke recovery, and learning: Scope and contributions to stroke rehabilitation. Neural Plasticity, 2019, 5232374. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5232374

Cho, E., Kim, M. J., Yang, M., Park, M. Y., Lee, H., Park, S., & Han, Y. (2023). Symptom-specific non-pharmacological interventions for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: Protocol of an umbrella review of systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials. BMJ Open 13, e070317. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070317

Colavitta, M. F., & Barrantes, F. J. (2023). Therapeutic strategies aimed at improving neuroplasticity in Alzheimer disease. Pharmaceutics, 15(8), 2052. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15082052

Colelo, K. J. (2021). Who pays for long-term services and support? Congressional Research Service, In Focus, IF10343. https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF10343

Diniz, C. R. A. F., & Crestani, A. P. (2023). The times they are a-changin': A proposal on how brain flexibility goes beyond the obvious to include the concepts of "upward" and "downward" to neuroplasticity. Molecular Psychiatry, 28(3), 977–992. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01931-x

Erickson, K. I., Hillman, C., Stillman, C. M., Ballard, R. M., Bloodgood, B., Conroy, D. E., Macko, R., Marquez, D. X., Petruzzello, S. J., & Powell, K. E. (2019). Physical activity, cognition, and brain outcomes: A review of the 2018 physical activity guidelines. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 51(6), 1242-1251. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001936

Genworth. (2024). Cost of care survey. Genworth Financial, Inc. https://www.genworth.com/aging-and-you/finances/cost-of-care.html

Karamacoska, D., Butt, A., Leung, I. H. K., Childs, R. L., Metri, N. J., Uruthiran, V., Tan, T., Sabag, A., & Steiner Lim, G. Z. (2023). Brain function effects of exercise interventions for cognitive decline: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17, Article 1127065. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1127065

Knapp, M., Bauer, A., Wittenberg, R., Comas-Herrera, A., Cyhlarova, E., Hu, B., Jagger, C., Kingston, A., Patel, A., Spector, A., Wessel, A., & Wong, G. (2022). What are the current and projected future cost and health-related quality of life implications of scaling up cognitive stimulation therapy? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 37(1), 0.1002/gps.5633. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5633

Kraal, A. Z., Dotterer, H. L., Sharifian, N., Morris, E. P., Sol, K., Zaheed, A. B., Smith, J., & Zahodne, L. B. (2021). Physical activity in early- and mid-adulthood are independently associated with longitudinal memory trajectories in later life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 76(8), 1495–1503. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa252

Matthews, K. A., Xu, W., Gaglioti, A. H., Holt, J. B., Croft, J. B., Mack, D., & McGuire, L. C. (2019). Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias in the United States (2015-2060) in adults aged ≥65 years. Alzheimer's & dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association, 15(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.3063

Mudrazija, S., Aranda M. P., Gaskin DJ, Monroe S., & Richard P. (2025). Economic burden of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias by race and ethnicity, 2020 to 2060. JAMA Network Open, 8(6), e2513931. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.13931

Nandi, A., Counts, N., Chen, S., Seligman, B., Tortorice, D., Vigo, D., & Bloom, D. E. (2022). Global and regional projections of the economic burden of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias from 2019 to 2050: A value of statistical life approach. EClinicalMedicine, 51, 101580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101580

National Association of Insurance Commissioners and the Center for Insurance Policy and Research. (2016). The state of long-term care insurance: The market, challenges, and future innovations. CIPR Study Series 2016-1.

Pickersgill, J. W., Turco, C. V., Ramdeo, K., Rehsi, R. S., Foglia, S. D., & Nelson, A. J. (2022). The combined influences of exercise, diet, and sleep on neuroplasticity. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 831819. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.831819

Rogers, J. (2023). McCance and Hurther’s pathophysiology: The biological basis for disease in adults and children. (9th Ed). Elsevier St; Louis MO.

Russell, D., Diamond E. L., Lauder, B., Digham, R., Dowding, D.W., Peng, T.R., Prigerson, H. G., & Bowles, K.H. (2017). Frequency and risk factors for live discharge from hospice. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(8), 1726-1732.

Shaffer, J. (2016). Neuroplasticity and clinical practice: Building brain power for health. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1118. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01118

Sikkes, S. A. M., Tang, Y., Jutten, R. J., Wesselman, L. M. P., Turkstra, L. S., Brodaty, H., Clare, L., Cassidy-Eagle, E., Cox, K. L., Chetelat, G., Dautricourt, S., Dhana, K., Dodge, H., Dröes, R. M., Hampstead, B. M., Holland, T., Lampit, A., Laver, K., Lutz, A., Lautenschlager, N. T., McCurry, S. M., Meiland, F. J. M., Morris, M. C., Mueller, K. D., Peters, R., Ridel, G., Spector, A., van der Steen, J. T., Tamplin, J., Thompson, Z., Bahar-Fuchs, A., & ISTAART Non-Pharmacological Interventions Professional Interest Area. (2020). Toward a theory-based specification of non-pharmacological treatments in aging and dementia: Focused reviews and methodological recommendations. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 17(2), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12210

Sturchio, A., Dwivedi, A. K., Malm, T., Wood, M. J. A., Cilia, R., Sharma, J., Hill, E., Schneider, L. S., Graff-Radford, N. R., Mori, H., Nübling, G., Ek Abdakiussi, S., Svenningsson, P., Ezzat, R., Espay, A. J., and The Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Consortia [DIAN]. (2022 Jan 1). High soluble amyloid-β predicts normal cognition in amyloid-positive individuals with Alzheimer’s disease-causing mutations. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 90(1), 333 – 348.

Sun, Y., & Zehr, E. P. (2019). Training-induced neural plasticity and strength are amplified after stroke. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 47(4), 223-229. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000199

Van der Steen, J. T., van der Wouden, J. C., Methley, A. M., Smaling, H. J. A., Vink, A. C., & Bruinsma, M. S. (2025). Music‐based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2025(3), Article CD003477. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003477.pub5

Velandia, P. P., Miller-Petrie, M. K., Chen, C., Chakrabarti, S., Chapin, A., Hay, S., Tsakalos, G., Wimo, A., & Dieleman, J. L. (2022). Global and regional spending on dementia care from 2000-2019 and expected future health spending scenarios from 2020-2050: An economic modelling exercise. EClinicalMedicine, 45, 101337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101337

White, L., Fishman, P., Basu, A., Crane, P. K., Larson, E. B., & Coe, N. B. (2019). Medicare expenditures attributable to dementia. Health Services Research, 54(4), 773–781. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13134

Yanagida, N., Yamaguchi, T., & Matsunari, Y. (2024). Evaluating the impact of Reminiscence Therapy on cognitive and emotional outcomes in dementia patients. Journal of Personalize Medicine, 14(6), 629. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm14060629

Yang, Z., & Levey, A. (2015). Gender differences: A lifetime analysis of the economic burden of Alzheimer's disease. Women's Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women's Health, 25(5), 436–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2015.06.001

Woods, B., Rai, H. K., Elliott, E., Aguirre, E., Orrell, M., & Spector, A. (2023). Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2023(1), Article CD005562. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005562.pub3

Zissimopoulos, J., Crimmins, E., & St Clair, P. (2015). The value of delaying Alzheimer's disease onset. Forum for Health Economics & Policy, 18(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1515/fhep-2014-0013