Scope of Advanced Practice for Nurses in the United Kingdom

Submitted by Barry Hill MSc BSc PGCAP DipHE RN

Tags: advanced practice apn clinical critical care ICU nursing leadership united kingdom

Nurses and midwives account for more than 30% of European healthcare professionals and hence have a very important and vital role to play in improving and driving up standards through leadership and management (Watkins, 2010). Donald et al. (2010) claim that there has been a lack of clarity of purpose for which the APN had been intended. It would seem appropriate to review the titling and definitions of the role. Historically many different job titles and job descriptions have existed for nurses with advanced practice skills (CHRE, 2009). Titles such as ‘nurse practitioner’ originated in the United States America (USA) and Canada in the 1960s, and it has been suggested other countries including Australia, United Kingdom (UK) and Ireland are still in their infancy stages with regards to recognition of advanced roles (Delamaire and La Fortune, 2010). The U.K. has a history of attempts to enable nurses to develop their skills for advanced practice since the 1970s (Stilwell, 1998). Origins of the advanced nurse in the UK are founded in the work of Stilwell (1988), with the introduction of a nurse practitioner role into primary healthcare. Stilwell’s (1988) nurse practitioner was an experienced nurse, using existing nursing skills with health assessment and diagnostic skills in autonomous patient management. Following this landmark work, nurse practitioner roles emerged in clinical practice during the 1990s and early 2000s (Carnwell and Daly, 2003).

Interestingly, APNs have proliferated only in the last decade. By contrast, other countries have witnessed increasing numbers and types of new APN roles such as “acute care nurse practitioners, advanced practice case managers and clinical nurse specialist, nurse practitioners” (Donald et al, 2010). The prevailing four models of APN within the UK consist of: clinical nurse specialists; advanced nurse practitioners: nurse consultants and matrons (RCN, 2005; RCN, 2009). With the exception of the APN, these titles themselves do not suggest that they practice at an advanced level because though highly specialised, they do not diagnose or treat autonomously. The Skills for Health (2006) document explicitly depicts advanced roles as including autonomous decision-making and expert clinical skills. Further re-enforcement can be found by the Nursing and Midwifery Council who state that only nurses who have achieved an Advanced Nurse Practitioner university programme are permitted to call themselves by this title, and it suggested that this must also have elements if not all, of master’s level of education (NLIAH, 2012). In 2008, the International Council of Nurses (ICN) has proposed a definition that included: “A Nurse Practitioner / Advanced Practice Nurse is a registered nurse who has acquired the expert knowledge base, complex decision-making skills and clinical competencies for expanded practice, the characteristics of which are shaped by the context and/or country in which s/he is credentialed to practice. A master’s degree is recommended for entry level” (ICN, 2008 a). The ICN definition has been the guideline for adoption by various countries. However, Bryant-Lukosius et al. (2004) suggests that advanced nursing practice refers to the work or what nurses do in the role and is important for defining the specific nature and goals for introducing new APN roles. The concept of advancement further defines the multi-dimensional scope and mandate of advanced nursing practice and distinguishes differences from other types of nursing roles. Advanced practice nursing refers to the whole field, involving a variety of such roles and the environments in which they exist. Many barriers to realizing the full potential of these roles could be avoided through better planning and efforts to address environmental factors, structures, and resources that are necessary for advanced nursing practice to take place. By comparison, the USA has defined, in detail, the APN as one who has built upon the competencies of registered nurses (RNs) by expanding knowledge and skills, completed and passed an accredited graduate level program meant for any one of the Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN) roles, acquired advanced clinical knowledge and skills so as to be able to give direct care to patients, and is well equipped for autonomous roles (Delamaire and Lafortune, 2010). Furthermore, within the USA, there is less difficulty in differentiating APN, as already, there are protected statutory titles of: clinical nurse specialists, nurse midwives, nurse anaesthetists, and nurse practitioners (Donald et al, 2010).

Perhaps the confusing terminology around the terms “advanced nursing practice “ and “advanced practice nursing” has had an impact on the acknowledgement and development of the ANP role. Advanced nursing practice refers to what nurses’ deliver as opposed to practice through specialisation expansion and advancement (Delamaire and Lafortune, 2010). ‘Advanced’ practice, it is argued, is a particular stage on a continuum between ‘novice’ and ‘expert’ practice (AANPE, 2012). Advanced nursing practice is distinct from basic nursing practice in that the former is specialisation or provision of care for a targeted patient population (AANPE, 2012). The latter, advanced practice nursing is a specific type of nursing practice depicted as a pyramid with environmental factors at the base warranting APN roles. Thus, APN is more than advanced nursing practice though it is basically of the same character. In order to further appreciate how and why interpretations of these advancing roles and titles have varied internationally, a discussion on some of the UK political, professional and cultural drivers will now take place.

UK Nurses have been waiting for approximately twenty-five years for the statutory body of the nursing profession to clarify the differing levels of practice. As far back as 1990, the United Kingdom for Central Council (UKCC) announced the setting up of the Post-Registration Education and Practice (or PREP) project aimed at raising standards for practice and education beyond registration (UKCC, 1990). The UKCC accepted that many specialist nurses were acquiring advanced skills and undertaking Masters and PhD level education. The UKCC said it would review this with regards to considering the recording of such qualifications in the future. However, in March 1994, the UKCC decided to set standards only for specialist but not advanced practice (UKCC, 1994) thus leaving ANPs in limbo with regards to official support in this advanced role. However, many other changes in healthcare were affecting modern day health and social care and began to impact on the role of the ANP. Two key changes were the implementation of both the Modernizing Medical Career initiative (DOH, 2005) and the European Working Time Directive (EWTD). This meant that doctors had a reconfiguration of their educational needs and reduction in their time allocated for training. It is suggested that the loss of doctors’ clinical time would have impacted upon the quality of front line care and service provision (Moonsinghe et al, 2011) and hence why the creation of ANP role was suggested. The Modernizing Nursing Careers initiatives, was published shortly afterwards (DOH, 2006a), promoting the advancement of nursing roles. This is one of the main political and professional drivers for the ANP role. This begs the question, were ANPs promoted to initiate changes in nursing or were they fulfilling workforce needs of the medical profession?

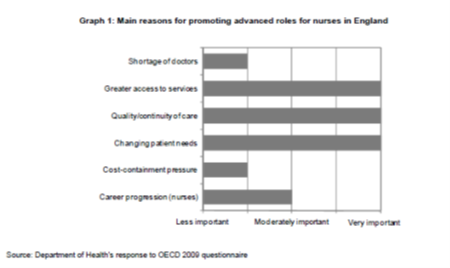

Literature would suggest that ANPs are physician’s replacements, thus possibly removing the identity ANPs deserve and further suggesting that nurses are bridging the gap between nursing and medicine (Bryant-Lukosius et al, 2004). Delamaire and LaFortune, (2010) highlight six important factors that are considered as the drivers pushing the APN career in England as seen from the graph below,

Reasons for promoting advanced roles for nurses in England as emphasised above are: the most important are greater access to services, quality and continuity of care, and changing patient needs rather than shortage of doctors. McKenna et al. (2006) believes that the ANP role creation is partly from pressure from the health service to cut costs. It seems that the need for advanced roles came from a combination of factors. Perhaps more important are the benefits of the ANP which will be discussed later.

Stilwell (1988) has emphasized the importance of the advanced practice role as a change agent for the creation of future nursing knowledge so as to achieve improved nursing and health care delivery. However, Donald et al. (2010) highlight some of the issues hampering the Advanced Practice Nursing (APN) role development which include: absence of role clarity and goal expectations; differing and confusing terminology between advanced nursing practice and advanced practice nursing; being viewed as a physician’s replacement and support and the surrounding factors belittling APN roles. Consequently, this essay will explore these issues in greater depth, and in particular review and discuss advanced practice relating to APN titles and definition, identity, and professionalism.

The Royal College of Nursing established formal training and education for prospective nurse practitioners in the UK in the early 1990s. The first educational competencies for nurse practitioners then emerged (RCN, 2008, revised 2010). These were based on consultancy skills, disease screening, physical examination, chronic disease management, minor injury management, health education and counseling. They enabled new curriculums to be structured on clear criteria that were quickly adopted in the UK as a gold standard. Universities around the country quickly developed programs of nurse practitioner education. Initially at diploma level, these soon evolved to undergraduate and then master’s level. Today, master’s level education is seen as a requisite for advanced nurses (Department of Health, 2010; Scottish Government, 2008). While the NHS required and desired advanced nurses, employers misunderstood the potential long-term contribution of those roles in terms of service redesign (Fulbrook, 1995). This was perhaps due to the lack of a structured clinical career framework to accommodate them at that time.

Within the UK, Scotland was the first country to produce a toolkit that had structure and gave the ANP identity through definition and implementation throughout the country (Scottish Government Health Department, 2008). Wales then followed this example with their own framework (National Leadership and Innovation Agency for Healthcare, 2012). In November 2010 the Department of Health (DOH, 2010) released a position statement on advanced level nursing that provided a benchmark to enhance patient safety and the delivery of high quality care by supporting local governance, assisting in good employment practices and encouraging consistency in the development of roles (DOH, 2012a p.4). Another key proposal was released by the Council for Healthcare Regulatory excellence (CHRE) for new roles and responsibilities the background for which came about from the white paper ‘Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS (DOH, 2010). It would seem that governmental and political strategies’ to support ANPs still haven’t been advertised to the public or implemented in the NHS whole-heartedly. According to the Royal Council for Nurses (RCN, 2012) Wales and Scotland appear to have implemented the role with success whereas in England it appears difficult to understand the professional identity of the ANP. In order to understand why some of these government strategies have been less effective at implementation of the ANP, it would seem pertinent to next discuss the issue of professional identity.

Professional identity appears to be an inherent problem in modern day British nursing regardless of level (Adams et al, 2006). This is supported by a research paper titled ‘Investigating the factors influencing professional identity of first-year students’ that sampled 1254 student nurses’ perceptions of professional identity via questionnaire. Adams et al. (2006) suggests that professional identity comes from perceptions from morals within nurses - before studying - depending on their individual qualities. Adams et al. (2006) further discussed the differences in strength of initial professional identity across professions, with physiotherapy students displaying the highest levels of professional identification (Adams et al, 2006). Holland (1999) suggests that student nurses develop their professional identity through a process of ‘undertaking the job hands on’ and socializing, albeit an ‘ill-defined transition’, on their journey to becoming qualified nurses (Holland, 1999). Regardless of the level of the nurse, it has been suggested that professional identities as well as the underpinning values are not fixed over time and might change (Fagermoen, 1997). An interesting research paper by Dellamaire and Lafortune (2010) considered an evaluation that was completed within 12 countries on the experiences of Advanced Nurse Practitioners. In summary these evaluations showed that nurses in these roles improve access to health care and improve hospital-waiting times. Also satisfaction of patients was increased when being assessed by ANPs and this can in itself empower the identity of the ANP (Dellamaire and Lafortune, 2010). Professional identity was also explored in Denmark that explored the impact of expanded nursing practice on professional identity, which was carried out in Denmark in 2012 (Piil et al, 2012). It explored the concept of professional identity and the experiences of five Danish nurses. The aim of this research was to investigate the impact of nursing assessments, demonstrating an expanded nursing role, their perception of autonomy, self-esteem, and confidence. The research used interviews to gain the nurses feedback. Piil et al. (2012) imply that nurses working within advanced professional practice view themselves as nurses and not as replacement doctors. The study also suggests that the involved nurses gained a higher sense of autonomy, self-esteem, and confidence in their practice. These elements have a positive impact on their professional identity. The research demonstrated that for the nurses working within advanced professional practice, the boundaries of professional practice have shifted significantly.

An important implementation to assist nurses in becoming recognized and promoting their identity was Lord Darzi’s NHS Next stage review report, High quality care for all (Department of Health, 2008), as it indicated a powerful change for the NHS in England focusing on quality of care along with access, volume and cost of health care. There was now recognition for experienced senior nurses for the delivery of the new NHS quality agenda; surely this contributes to the value of nursing leadership? To the writer, it is imperative that continued development, educational courses, and implementation of the role is continued. ANPs are of paramount importance to the health care system, as their scope of practice allows distribution of their experience and clinical expertise (RCN, 2012). This is supported by the ‘modernizing nursing careers’ document, which expresses moving away from subservient nursing practices (DOH, 2006), and moving forward into autonomous evidenced based practice, questioning clinical practice, and in essence, improving identity.

Within the RCN document ‘breaking down barriers and driving up standards’ the role of the senior nurse was described to be inclusive of leadership and management, clinical practice, and education and teaching (RCN, 2009). However, there were multiple conflicts’ that would impact on the nurses’ professional identity. For example, the absence of agreed role definitions and clarity about role aims, purpose and functions. Role conflict was another concern, suggesting that ward sisters, for example, are constantly balancing the different aspects of their own roles (RCN, 2009).

Advanced nurse practice permits clinical leadership with autonomy, and is an interesting diversion from a typical management role, hence this is an appealing alternative for nurses who do not want to become managers, who want to practice clinically or teach. Within Critical Care (which is the writer’s area of clinical practice), advanced practice nursing titles consist of Advanced Critical Care Practitioners (ACCP) and Advanced Nurse Practitioner in Critical Care (ANPCC) (DOH, 2008). The role of the ACCP assumes many of the medical roles but maintains a nursing focus (DOH, 2006). The ACCP can assess, plan and implement care, but also should be able to perform advanced assessment, diagnosis, prescribe medication and therapy if it is within their scope of practice (DOH, 2008). Initially, the prospect of highly experienced nurses within critical care performing such tasks appears to be of natural advance to their scope of practice, but the writer cannot help but wonder what how their identity is seen by both patients and staff. This is where literature becomes interesting, as the nurses taking on extended responsibilities (normally performed by doctors) will be judged against the GMC competencies in a court of law, but in essence they are nurses are indeed nurses (Llewellyn and Day, 2008). This is just one example of how identity, even within clinical practice, can impact the identity of ANPs. ACCP continue to seek regulation. Advanced practitioners continue to be registered with the Nursing and Midwifery Council or Health Professions Council as the case may be depending upon the discipline, however, it is suggested by Boulanger (2004) that a separate identity for ACCP should have a single regulator regardless of the background of their discipline (Boulanger, 2004).

In conclusion, extensive amounts of literature exist that discusses advanced practice nursing roles, the identity of these professionals, and their contribution to healthcare delivery in various countries. However, lack of consistency around title, role definition and scope of practice remains. It is evident from literature that the need for ANPs is there. With regards to identity, this appears to evolve and change with time. Early literature had discussed nurses following doctors’ orders, but this was in a time when hospitals had less acute patient groups, and the community having less chronic lifelong illnesses. Order and authority ruled and task oriented care within nursing was standard. Now in the UK, it appears as though nurses are gaining recognition for their status and professional identity. Nurses are now a graduate only profession. It is felt that with the current redesign of the NHS, that possibly once again there might be tiered nursing workforce - with the developments of band 4 health care practitioners, bridging the gap between health care assistance and registered nurses, similar to the state enrolled nurses, within agenda for change, as well as modern matrons, and many other new roles as discussed earlier in this paper. The identity of nursing is strong, yet confusion exists over random titling, and the use of uniforms, professionalism and various other opinions of the public and the multidisciplinary team, but nurses are the biggest group in healthcare. Literature has suggested that the identity of the ANP within the UK came from the toolkit from Scotland. But nurses were assessing and semi-diagnosing patients in the USA in the 1960s - albeit unrecognized, it was happening.

The author believes that the identity of the ANP is sturdy. The government has put a great deal of effort into promoting the ANP role in all the strategies discussed within this essay, with particular emphasis on the PEPPA framework, which is helping employers install the role within healthcare in the UK. Full regulation would promote the role further and hopefully would assist experienced senior nurses to practice independently with appropriate support from their employers. As stated in the above literature, without adequate doctors in both acute and primary care, solutions have to be found immediately. Ageing and expanding populations, mass migration to the UK increasing the size of the population and employers not funding or allowing their senior staff to step up and take on the challenges of modern day health care will result in an unsafe and understaffed workforce in the future. It is felt and hoped by the author that with all the strategies and support that is currently out there for ANPs, their identity can only grow and will be key in delivering holistic, patient focused, quality of care to patients. It would also assist their employers and the government in achieving targets such as: reduction in hospital admissions through rapid response community nursing, reduced hospital stays, as nurses will be diagnosing and prescribing, so that patients will not have to wait to see the doctor the next day, or stay the weekend because the consultant works Monday to Friday. Patients should be seen earlier, diagnosed and treatment started immediately within the nurse’s scope of practice and clinical specialist area.

Already senior nurses within ICU are relatively autonomous. The unit is clinically led by the Charge Nurse of ICU, and medically led by the ICU consultant, so the ACCN role appears to be of natural progression for the experienced senior nurse within critical care. ICU outreach nurses already act as autonomous practitioners within advanced practice, assessing, diagnosing and commencing treatment on critically ill patients on the wards, and preventing admissions into ICU. This only promotes the identity of the ANP within ICU. With appropriate local agreements and scope of practice discussed, it will lead the way to higher standards and quality of care, thus empowering the nurse and also empowering the nurses’ identity. It is now the author’s mission to promote the role of the ANP within his work area and educate his place of work with the initiatives to implement this role properly with appropriate training, in conjunction with a job description that fits what he will be required to do.

Bibliography and Reference List

- AANPE (2012) Development of Advanced Nursing Practice - A Toolkit Approach [Online] Available from: http://www.aanpe.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=giFsLijsCRw%3D&tabid=1 051&mid=2508&language=en-US [Accessed: 08.12.12].

- Adams, K; Hean, S; Sturgis; P. and Macleod, J. (2006) investigating the factors influencing professional identity of first-year health and social care students. Learning in Health and Social Care. 5 (2), pp. 55–68.

- Boulanger, C. (2008) The Advanced Critical Care Practitioner: trailblazing or selling out? Journal of Intensive Care Society. 9 (3), pp. 216-217.

- Bryant-Lukosius, D; DiCenso, A; Browne, G. and Pinelli, J. (2004), Advanced practice nursing roles: development, implementation and evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 48 (5), pp.519-529.

- Council for Healthcare Regulatory Excellence (2008) Advanced Practice: Report to the Four UK Health Departments. [Online] Avaliable from: http://www. tinyurl.com/Council-advanced [Accessed: 24.08.13].

- Cohen H.A. (1981) The Nurse’s Quest for A Professional Identity. Menlo Park, California: Addison-Wesley.

- Darzi, A. (2008) High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report. London: Department of Health, 2008.

- Delamaire, M. and LaFortune, G. (2010) Nurses in Advanced Roles: A Description and Evaluation of Experiences in 12 Developed Countries. OECD Health Working Papers, No. 54, OECD Publishing.

- Department of Health (2004) Modernising nursing careers: Setting the direction. [Online] Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@ en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4138757.pdf [Accessed: 10th December 2012].

- Department of Health (2005) Modernising Medical Careers. London: Department of Health.

- DOH (2006a) Modernising Nursing Careers – Setting the Direction. [Online] Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4138756 [Accessed on: 07th December 2012].

- Department of Health (2008) The National Education and Competence Framework for Advanced Critical Care Practitioners. [Online] Available from: http://tinyurl.com/advanced-criticalcare [Accessed: 10th December 2012].

- DOH (2008) High quality care for all: NHS Next Stage Review final report. [Online] Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_085825 [Accessed: 25th November 2012].

- DOH (2010) Equity and excellence: Liberating the NHS. [Online] Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_117353 [Accessed: 22nd November 2012].

- Donald, F; Bryant-Lukosius, D;Martin-Misener, R; Kaasalainen, S] Kilpatrick, K; Carter, N; Harbman, P;Bourgeault, I and DiCenso, A. (2010) Clinical nurse specialists and nurse practitioners: title confusion and lack of role clarity. Nursing Leadership. 23, pp.189-201. Available from: http://www.longwoods.com/content/22276 [Accessed 10th August 2013].

- Fagermoen, M. (1997) Professional identity, values embedded in meaningful nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 25, pp.434-441.

- Ford (2009) Nursing Degrees. [Interview] 12th November 2009 [Online] Available from: http://www.nursingtimes.net/whats-new-in-nursing/news-topics/health-policy/all-new-nurses-must-have-degrees/5008452.article [Accessed 10th December 2012].

- Grossman, S and O’Brien, M. (2010) How to Run Your Own Nurse Practitioner Business: A Guide for Success. New York, Springer Publishing company. pp. 1-20.

- ICN (2008) Definition and characteristics of the role. [Online] Available from: www.icn.ch/networks.htm [Accessed: 17th December 2012].

- Llewellyn, L.E and Day, H.L. (2008) Advanced nursing practice in paediatric critical care. Paediatric Nursing; 20 (1) pp. 30–33.

- Lucey, C and Souba, W. (2010) Perspective: the problem with the problem of professionalism. Academic Medicine. 85 (6), pp.1018-24.

- McKenna, H; Richey, R and Keeney, S. (2006) The introduction of innovative nursing and midwifery roles. Journal of Advanced Nursing 56 (5), pp.553-562.

- Moonsinghe, SR; Lowery ;Shahi, N; Millen, A and Beard JD. (2011) Impact of reduction in working hours for doctors in training on postgraduate medical education and patients’ outcomes: systematic review. BMJ, 342.

- NLIAH (2012) Framework for Advanced Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professional Practice in Wales. National Leadership and Innovation Agency for Healthcare. [Online] Available from: http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sitesplus/documents/829/NLIAH%20Advanced%20Practice%20Framework.pdf [Accessed 15th November 2012].

- Piil, K.; Kolbaek, R; Ottmann, G and Rasmussen, B. (2012) The impact of the expanded nursing practice on professional identify in Denmark. Clinical Nurse Specialist. 26 (6) 1, pp.329-35.

- RCN (2005) Maxi Nurses. Advanced and Specialist Nursing Roles, Royal College of Nursing. London.

- Royal College of Nursing (2008, revised 2010) Advanced Nurse Practitioners – an RCN Guide to the Advanced Nurse Practitioner Role, Competences and Programme Accreditation. Available from: http://www.tinyurl.com/RCN-advanced-nurse [Accessed on: 24.08.13]

- RCN (2009) Breaking Down Barriers, Driving Up Standards. RCN: London.

- RCN (2012) RCN Competencies: An RCN guide to advanced nurse practice, advanced nurse practitioners and programme accreditation. [Online] Available from: http://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/146478/003207.pdf [Accessed 16th December 2012].

- Scottish Government Health Departments (2008) Supporting the development of Advanced Nurse Practice. [Online] Available from: http://www.aanpe.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=giFsLijsCRw%3D&tabid=1051&mi [Assessed 1st December 2012].

- Skills for Health (2006) Career Framework for Health [Internet] Bristol, Skills for Health. [Online] Available from: http://www.skilllsforhealth.org.uk/page/career-framework [Accessed 13th December 2012].

- Stilwell B (1988) Patients’ attitudes to a highly developed extended role: the nurse practitioner. Recent Advances in Nursing; 21 (1), pp.82-100.

- UKCC (1990). Post-registration education and practice project (PREP). Register no 6. London: UKCC; 1990. pp.4–5.

- UKCC (1994). The future of professional practice – the Council’s standards for education and practice following registration. London: UKCC.

- Watkins, H (2010) An Overview of the Role of Nurses and Midwives in Leadership and Management in Europe. [Online] Available from: http://www.institute.nhs.uk/images/documents/An%20overview%20of%20the%20role%20of%20nurses%20&%20midwives%20in%20leadership%20and%20management%20in%20Europe.pdf [Accessed 01st January 2013].